For years we (the archivists) had grappled with what to do with our electronic records. But in 2018 a couple of things happened that made us realize we really needed to make headway. Up until then, our digitized content was saved onto what we called “scribe drives” which were server drives mapped to our computers. In 2017, we digitized nearly 10 ¼-inch audio reels in the Genie Chance papers, which took up a lot of space, however we could still make do.

But in 2018 we received a request to digitize two 16mm film reels from the Dorothy and Grenold Collins papers. When we sent the film to our vendor, we had it digitized both in high (uncompressed 1080p AVI) and low resolution (h.264, mp4). This would allow us to have a master copy of the film, as well as an access copy. The films’ runtimes were 46 minutes and 34 minutes. The AVI files were both nearly 360 GB, which amounted to nearly one terabyte of data to add to our scribe drives, but we couldn’t. We had maxed them out.

CDs from the Anne Nevaldine papers

Around the same time, we also received the Anne Nevaldine papers. The collection had 4 boxes of 35mm slides, and two stacks and one container of CDs. I had a volunteer put the CDs through our segregation machine and scan them for viruses. (We actually had one CD that had a virus on it, which was, I believe, the first time that happened. We gave the disc to the Library’s IT Department, who were able to remove the virus and gives us our files). The student also saved all of the discs onto an external hard drive. In the end, the digital content of the Nevaldine papers was 315 GB.

A couple weeks after the finding aid for the Anne Nevaldine papers went live, a researcher came in to look at the photographs. She knew Anne, and wanted a reproduction of one of Anne’s photos to be used in a local garden club newsletter. This created an issue. All of the digital files were only on an external hard drive, which had not been backed up yet. And they were high resolution Canon Raw (CR2) files. The researcher computer in the Research Room would not open the CR2 files, and we had no way to ensure the integrity of the files and that the researcher would not accidentally delete them.

Around the same time, I (Veronica), knew I wanted to apply for a couple of grants to digitize some of the audio, video, and film in our collections that was currently inaccessible to researchers unless they paid out of their pockets for the digitization. (For more information regarding these grants, please read: Getting the Grants: Atwood Foundation and CLIR RAR) By this time, our vendor had the option of scanning the 16mm films in 2K, which is a better quality than the 1080p, but also would make the file sizes even larger.

Having the Collins films digitized, the Anne Nevaldine acquisition, and the possibility of receiving two grants, we knew we had to do something. We decided we wanted to have a system where we could save and access all of our digital content, as well as having it backed up, and a way to make read-only copies available to researchers in the Research Room. We initially approached the University’s IT Department to see what we could do. We knew we would probably end up having nearly 5 TB of data right off the bat if we factored in our current digital items and the possibility of future ones. Unfortunately, we were quoted a very high cost by the University’s IT Department. So, we approached the Library’s IT Department for suggestions. After some discussion about what would be appropriate for our needs, Brad, the Library’s PC and Network Administrator, presented us with some options.

We ultimately decided on a Synology DiskStation DS1817+, which cost $848, with WD Gold 10TB HDD drives. We settled on 8 drives (to provide growth space), which cost $375 each for a total of $3000. Then we need a system to hook it to. For that we just used a Windows 10 Desktop, which cost $1065. The total cost was $4913, however we also needed a cloud service provider to backup the files. We ultimately decided to go with Backblaze, which costs $5 a TB per month.

The NAS

This whole system is a network-attached storage system, which means it is a file-level computer data storage server connected to a computer network. We took to calling it “the NAS” for short. After pricing everything, we had to go to Dean Rollins and ask for funding, and he agreed.

After our new system was hooked up, we then had to transfer the files to it and develop a new system for arranging and saving the files. Ultimately, we decided on having three separate drives, two of which would be on the NAS (Master and Access), and one a separate network drive (Reference_Access). The Master drive is the only one that is backed-up to the cloud service provider, Backblaze. Once materials are saved onto the Master drive, they will not be accessed. The Master drive is to act as a dark archive. Therefore, we created the Access drive where archivists can retrieve the digital contents for reference and use purposes. Access is essentially a copy of the Master drive. There is also a Reference_Access drive, which is mapped separately to each computer within the Archives, and not on the NAS. Reference_Access is the drive our users will use to access digital content while they are in the Research Room and contains the access copies and low resolution jpgs of photographs that may be high resolution in the Master and Access drives. The Reference_Access drive on the researcher computer in the Research Room is a read-only drive, which means that users cannot make changes to any items within this drive.

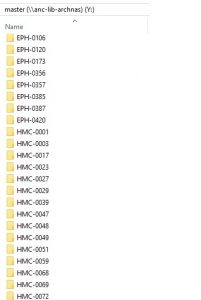

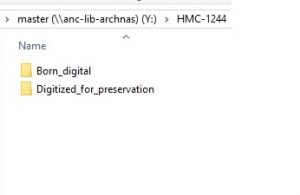

Transferring the files to the new system took about three months of in-consecutive work (I had other projects pop-up during this time and saving 350 GB files takes a while), which could not have been completed without the help of Megan, our volunteer at the time. Our former method of saving digital content was not consistent and we would save items under the collection name, which occasionally created multiple folders for the same collection depending on how the person creating the folder named it. So, we decided that all digital materials would be saved within their collections using the collection call number as the main folder name (i.e. HMC-0001). Within each of these, we decided that there would be three main sub-folders reflecting the type of digital records: Born digital (items that were created electronically), digitized for preservation (items digitized for preservation purposes, such as nitrate photographs, A/V materials, or heavily damaged documents and photographs), and digitized for reference (photographs and documents digitized at high resolution for reference requests).

Our files are now organized

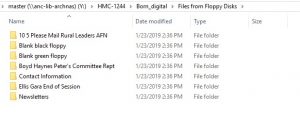

Two of the digitized files within the Johnny Ellis papers

The files within the Born_digital folder of the Johnny Ellis papers

The next step was mapping the Reference_Access drive to the researcher computer in the Research Room, and to make it read-only, but only for that computer. After working with the University’s IT Department, Brad was able to make it work. Since it was mapped last spring, the Reference_Access drive has been used by multiple researchers and it works great! They are able to access digital content of collections as easily as looking through a box on a table. And we could not have done it without Brad and Megan’s help, or Dean Rollins for agreeing to give us the funding for the system. We are grateful for all they did and for having a great mechanism for saving our electronic records, at a relatively low cost.