“So, what does an archivist do?”

It’s a question I hear a lot from pretty much everyone, from researchers and other faculty members, to people I meet in my everyday life. I generally give them the short answer, which is that I preserve and make accessible papers and records, such as diaries, photographs, and business records, of people and organizations, with a particular focus on the Southcentral Alaska region.

But sometimes people want to know what I actually do all day, and I usually spend ten minutes or so answering the question because my job is so varied. People who have never done research in archives, or who have used archives where the archivists are more specialized, are often shocked to find out about the sheer variety of different things I do, even in a single day. So, I thought I would write a post about a day in my life as an archivist (it happened to be Friday, September 2, in case you were wondering).

8:30 AM: I arrive at the archives. I have a reference shift in the morning, so I drop my purse in my office, fill up my water bottle in the break room, and take my place at the reference desk

8:35 AM-8:45 AM: I check my personal email, as well as the Archives and Special Collections email account. We get reference questions through email and over the phone, as well as in person. During a given reference shift, I may receive and answer reference questions about our collections (or other informational questions) through any or all of these channels. On this particular morning, we have one email from the UAA Advancement Office asking to set up a time to speak with us about doing publicity for our upcoming Sharing Community Images Project event. I respond that their office can call us any time between 10:00 AM and 4:00 PM.

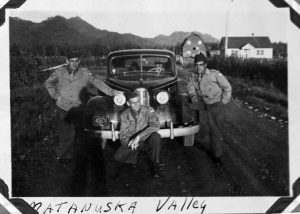

8:45 AM-11:00 AM: I begin creating metadata for photographs from the Lelon E. Alexander papers to be added to Alaska’s Digital Archives. The photographs are from the scrapbook of a soldier with the 714th Railway Operating Battalion, which operated the Alaska Railroad during World War II. The photos show a different side of the war, as well as soldiers having fun.

Lelon Alxander and other soldiers in front of a store in Moose Pass.

One way that we try to increase access to our collections is by digitizing a small amount material and putting it on the Digital Archives. This allows people all over the world to get a glimpse of what we have. Plus, Alaska’s Digital Archives is a partnership between a number of institutions, so people can see things from all over the state.

Putting the photographs on the Digital archives requires adding them to a program that uploads them, along with metadata, to the Digital Archives server. The metadata consists of specific information about the photos, such as the photographer’s name, the collection name, and the subject. Often the information has to be typed in a particular format (for example dates are year, month, day) or use specific (often seemingly arbitrary) terms (such as “Fuel wood” for wood that is meant to be burned in a fire or stove). This standardization makes materials more searchable and, ultimately, easier for researchers to find.

11:00 AM-11:15 AM: I post side by side pictures of Creek Street in Ketchikan, Alaska, from the 1940s and the present, to the Archives Twitter account. This year, we have been taking a virtual tour of Alaska on Twitter and Facebook. Each week, one of us picks a location and posts photos or documents relating to the place using the hashtag #AKPlaces. We also have an online exhibit for people to look at the places we have already “visited” if they missed them on social media. I chose Ketchikan because I had recently been there and wanted to do at least one post with both a historical photograph and a current one.

11:15 AM-11:30 AM: The historian for one of the organizations whose records we hold, brings by several binders of meeting minutes and other records to be added to the collection. She also drops off an updated deposit agreement, signed by the president of the organization. We typically have organizations still in existence sign one of these agreements allowing the Archives to provide access to materials, while the organization retains ownership over them. I create an accession record in Archivists’ Toolkit, the archival management software that we use to keep track of information about our collections. The accession record is the initial record we create when we receive new material, before it is added to an existing collection or an entirely new collection is created.

11:30 AM-11:35 AM: One of our regular researchers arrives. She is working on a dissertation about health in the circumpolar region and requests several boxes from the William W. Richards papers. Richards was U.S. Public Health Service psychiatrist who studied social transitions in the North. I bring her the boxes from the locked vault where we store our collections and log the interaction in the database we use to track our reference requests. The database helps us gather statistics about patterns of use, which allow us to make decisions about things like what materials to digitize or what collection should be next in our ongoing effort to update our collection guides. It is also useful to have a way to keep track of reference interactions and not accidentally email a researcher the same exact thing twice.

11:35 AM-1:00 PM: I continue adding metadata to the Lelon Alexander photographs for the Digital Archives until the end of my reference shift.

1:00 PM: Lunch! One of my colleagues ordered Falafel King. This is clearly the highlight of the day.

1:00 PM-2:30: As part of an ongoing project to update the guides to our collections, I’m converting the guide to the Harry and Norma Hoyt family papers to our current finding aid template. The collection is contains the papers and photographs of a family that was involved in fox farming and running the Gulkana Roadhouse, and later operating Hoyt Motors in Anchorage. The new format is easier for researchers to use, as well as being more in line with accepted archival standards. Often, in the process of updating a collection guide, it becomes necessary to reevaluate the content or arrangement of a collection. One example of this is transferring published materials, such as books or reports containing annotations, to the Rare Books collection. In the case of the Hoyt papers, the photographs had been removed from a number albums and rearranged by size. Part of the work I am doing on this collection (with the help of student workers and volunteers) is returning the photographs to their original order within the albums so that they are easier to find.

2:30 PM-4:30 PM: I attend a monthly Faculty Senate meeting. I spend the meeting taking notes to send out to the rest of the library Faculty. Faculty Senate is a great way to represent the Archives in a university-wide forum, stay informed about and involved in university issues, and meet other faculty members.

4:30 P.M.-5:00 PM: I continue working on the finding aid for the Harry and Norma Hoyt papers until it is time to go home.

Thank you for sharing. I have been interested I MLIS and archives and this was very informative.

Thanks so much for posting this! I’ve been considering getting a Master’s in Public History/Library Science and this is super helpful.